Root canal therapy of a molar tooth was a sophisticated treatment 50 years ago: the extraction was the rule.

Endodontics of a molar tooth is still a sophisticated treatment today, but it has become a normal dental procedure in any dental office.

What has changed? Tools, techniques, mentality of the dentist and patient needs.

Dentists today are used to working in very narrow spaces.

Progress in some surgical disciplines, such as periodontology and implantology, has been extraordinary.

Oral surgery, however, was excluded: the tools and techniques for the extraction of wisdom teeth are the same as 50 years ago, even in the video clips we see today on the Internet.

The contrast is even more striking when we consider that dentists safely perform sinus lift procedures in their offices, while referring cases of cysts to hospitals. Yet, the elevation of the sinus membrane requires greater skill than the detachment of a cyst wall.

Elevation of the sinus mucosa after a micro-antrostomy. This delicate maneuver allows you to keep the sinus membrane intact before proceeding to the filling.

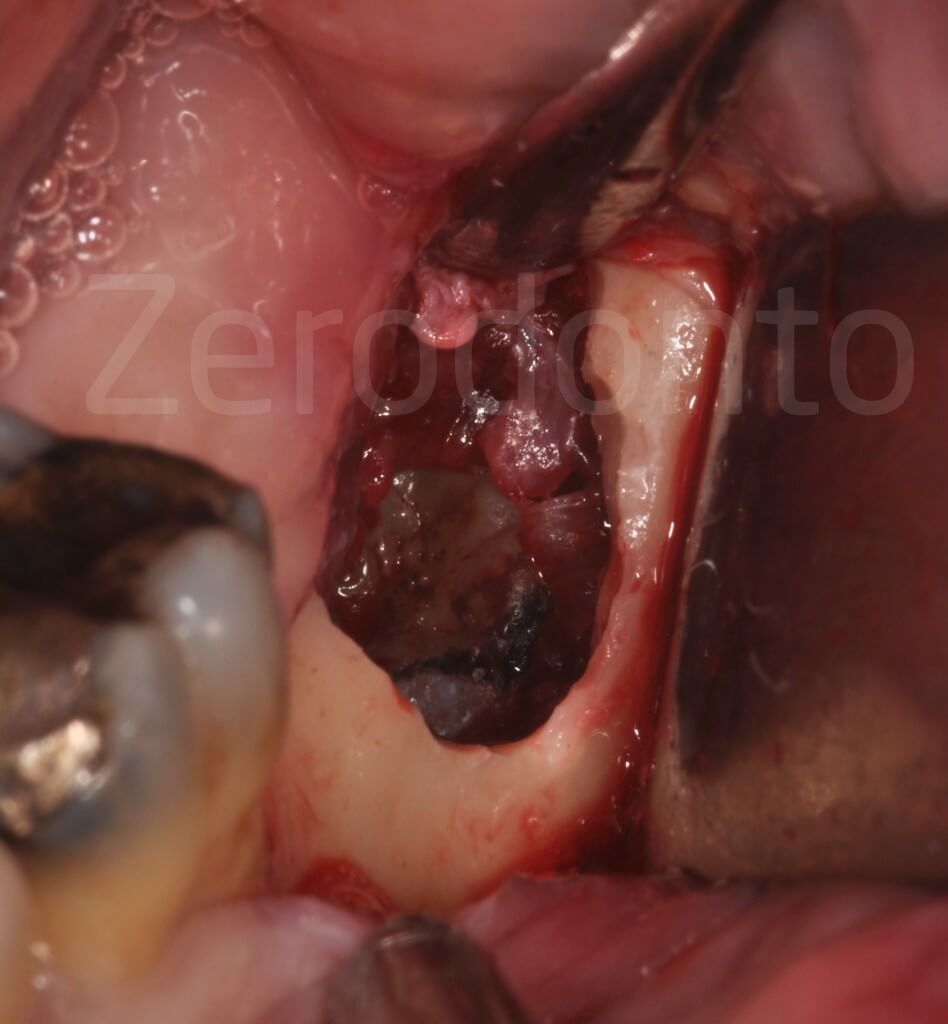

A case of cystic lesion associated with the impacted wisdom tooth (surgery under local anesthesia)

The video clip starts where the impacted tooth has already been extracted. We remove the cyst by means of dissection with surgical curette and gentle traction with biopsy forceps, through the osteotomy used for extraction.

The dissection technique is similar to a micro-antrostomy.

The periodontal bone peaks of the second molar and the external oblique line were preserved.

We believe the time has come to align oral surgery to today’s high dentistry standards to carry out even complex oral surgery in the office safely and without stress.

Surgery can become complex as a result of:

- limited access (eg. target depth)

- risk of damage (eg. to the inferior alveolar nerve)

- unusual cases and aggressive diseases (eg. keratocysts)

- systemic conditions (eg. anti-coagulant therapy)

These factors often overlap and complicate each other.

Solving complex cases requires:

- diagnostic competence

- effective anesthesia

- adequate instruments

- rational method of operation

Prejudices are another source of complexity:

1. Cone beam (CB) is frequently used as a first-level examination for wisdom teeth.

However, the examination which identifies the risk is the panoramic radiograph (Rood & Shehab, 1990).

The CB is a second-level examination (SEDENTEXCT, 2016) which serves to identify the lingual or buccal location of the alveolar canal relative to the roots when the intersection between the two structures is at the height of the furcation or at the middle or coronal third of the roots.

2. Anesthesia without epinephrine.

Epinephrine (1: 100,000) is necessary to obtain a sufficient duration and depth of anesthesia and is indicated in most heart conditions (Brown & Rhodus, 2005) because it prevents the incretion of norepinephrine.

3. The nerve block is dangerous.

In studies with a large sample size (more than 10,000 cases) no neurological damage was observed (Arcuri et al, 2004).

4. High speed handpieces can produce emphysema and bone necrosis.

Emphysema is impossible because the 45° surgical handpieces do not emit air into the operative field. The handpiece is obviously not indicated for implant surgery where the loss of vitality even of a few cell layers may compromise the osseointegration. The loss of some osteocytes does not cause clinically significant consequences in extractive surgery.

Good results depend on proper and neat surgical actions.

No diagnostic test and no surgical instrument can prevent injury from poorly planned or poorly executed surgery.

Let’s see three illustrative case reports.

CASE 1

Pain and repeated abscesses in a 70 year-old male patient, with heart disease, taking anticoagulant therapy

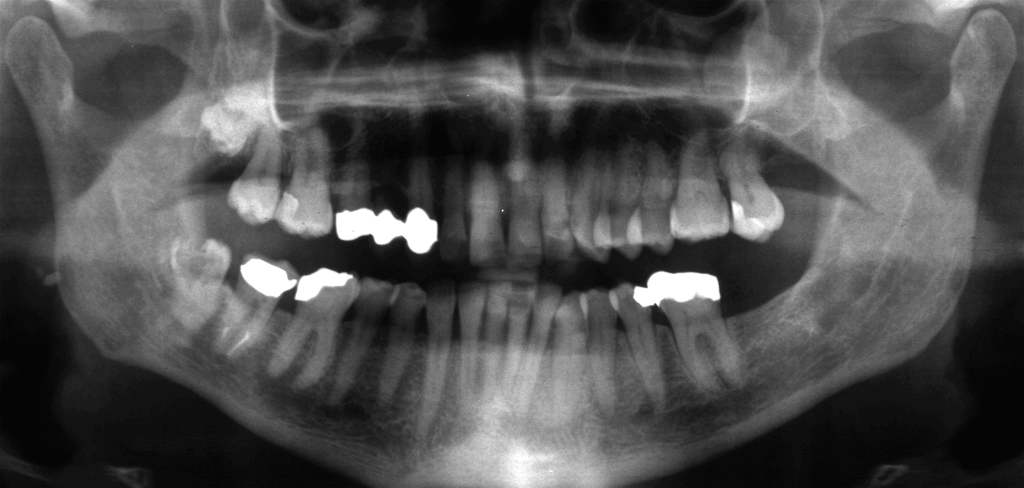

The left mandibular third molar is very deep, carious, with a radiolucent area around the crown. The anatomic relationship with the alveolar canal is at risk: the roots appear radiolucent where they cross the canal.

Medical history: heart attack two years ago, currently taking anticoagulants and candidate for heart surgery for stent and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy.

Rationale for surgery: need to remove the infected tooth before heart surgery.

Complexity factors: impairment of general health, anticoagulants, deep impaction associated with erosion of the lingual cortical plate and radiolucency of the middle third of the roots where they cross the alveolar canal (Rood & Shehab, 1990).

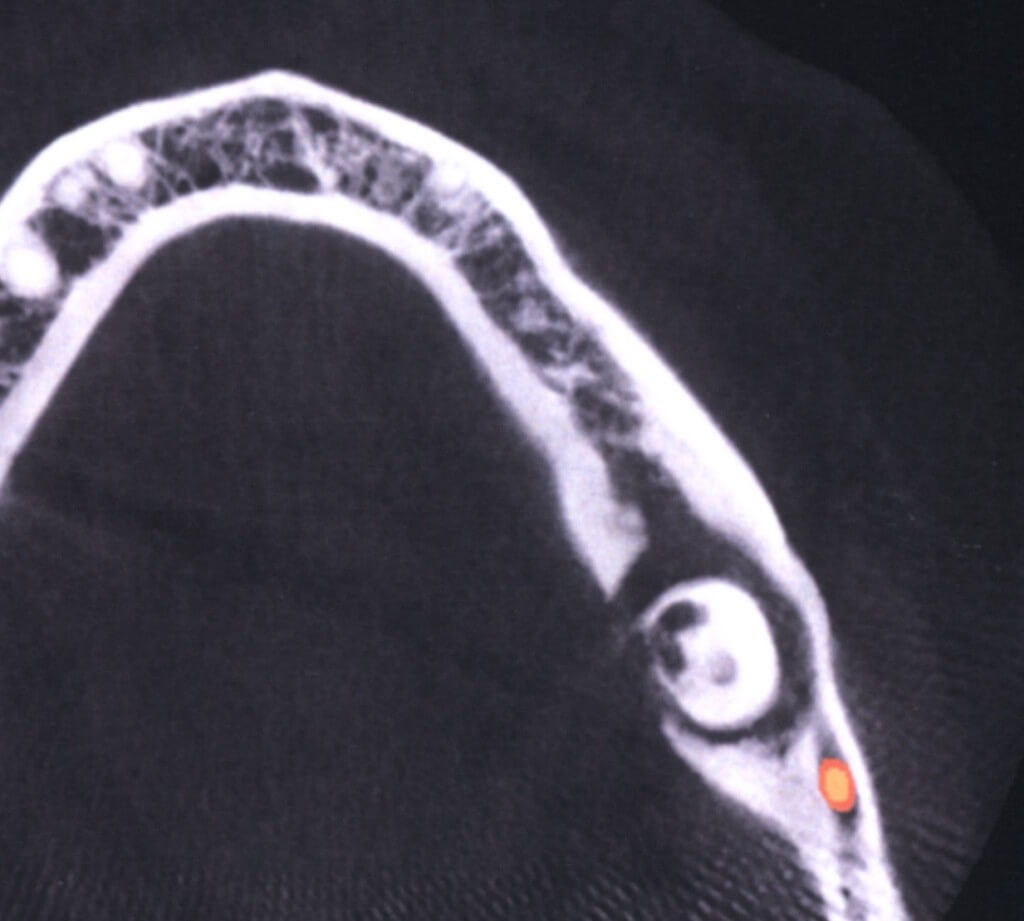

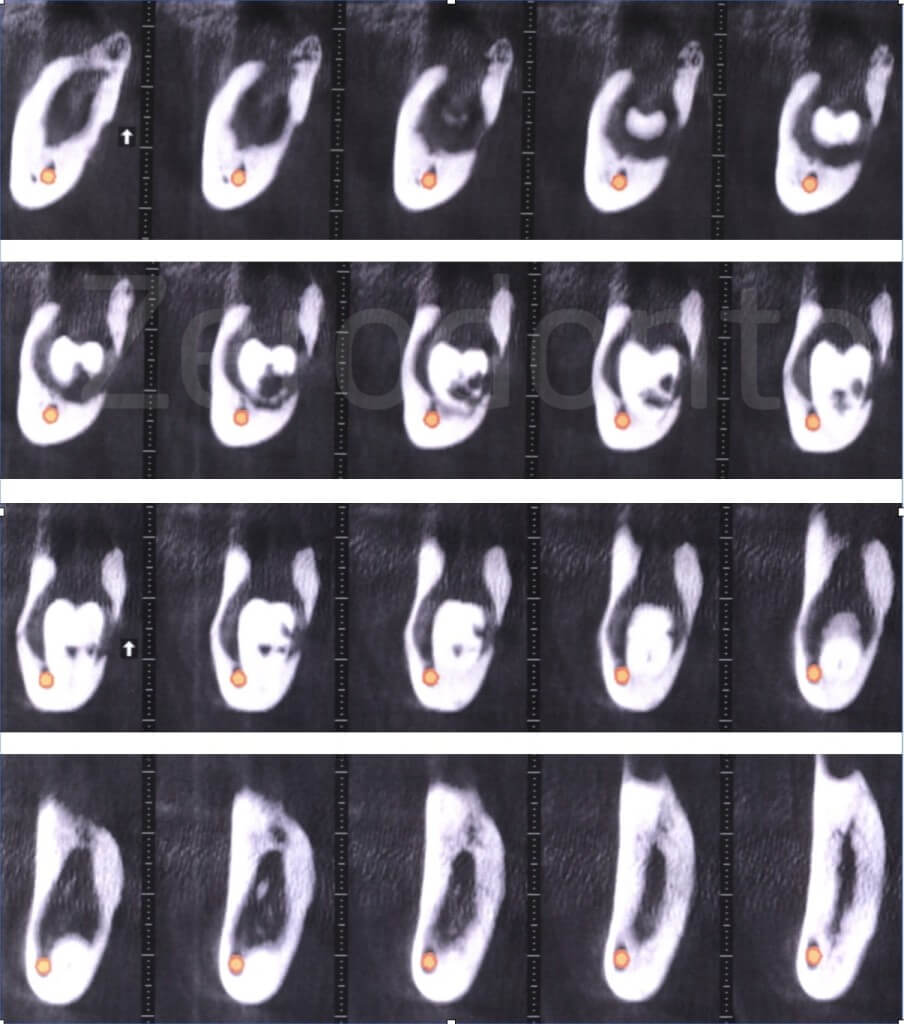

A Cone Beam was requested.

The impacted tooth is carious and the lingual cortical bone is eroded.

The alveolar canal is buccal to the roots of the impacted tooth, the apexes are located in close proximity of the basal edge of the mandible and the lingual cortical plate is eroded in a deep portion.

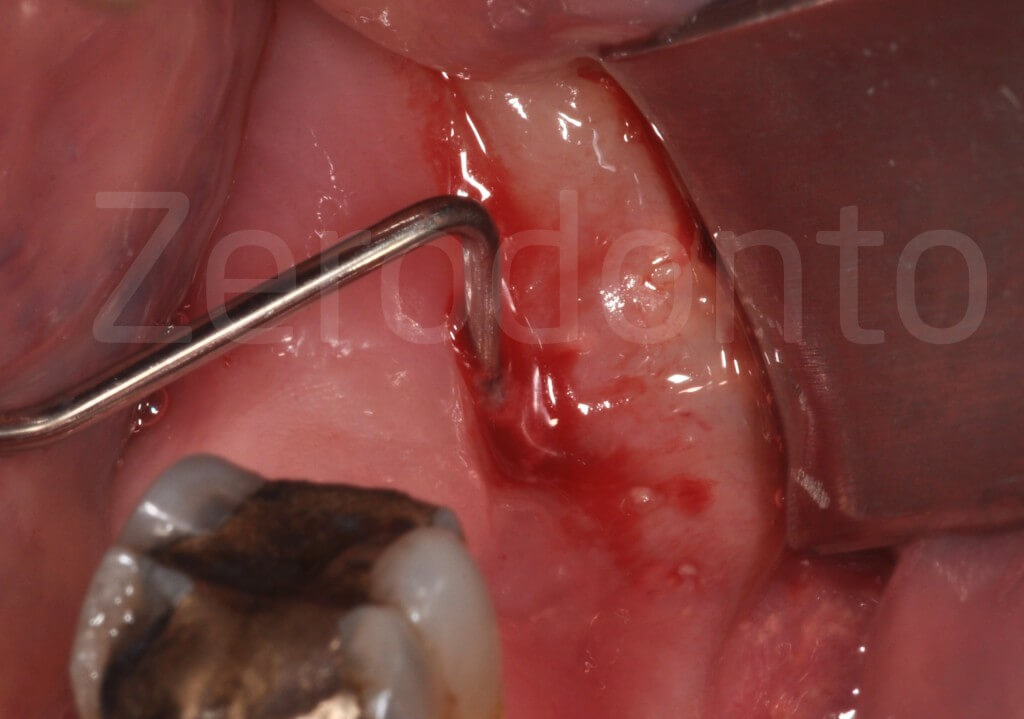

A periodontal probe penetrates into the fistula more than 15 mm, before reaching the impacted crown.

Strategy to address the complexity factors

- compromised general health:

operating prior to cardiac surgery, local anesthesia with epinephrine (Brown & Rhodus, 2005)

- anticoagulant therapy:

assessing INR the day of surgery (< 2.5) (Weltman et al, 2015)

- deep impaction and lingual erosion:

45° handpiece, long burs, Friedman elevators

- proximity to the alveolar canal:

sonic tips

An incision corresponding to the fistula, a releasing incision directed distally and buccally, and an incision in the sulcus of the first molar, delimit a triangular flap.

Bone resection with preservation of the external oblique line and the partial removal of the infected soft tissue allow the crown of the deeply impacted tooth to be visible.

Technical steps in the video clip

- Removal of the soft tissue around the crown with a curette

- Incomplete division of the crown with a long drill, fracture with elevator and removal of fragments

- Profuse bleeding makes it difficult to see the roots near the alveolar nerve at the bottom of the wound

- The sonic tip (Komet, SFS 90 M / D) and operating microscope optimize visibility and minimize the risk of neurological damage. The sonic vibration tips are shaped to create a space to insert a thin elevator between the bone and root

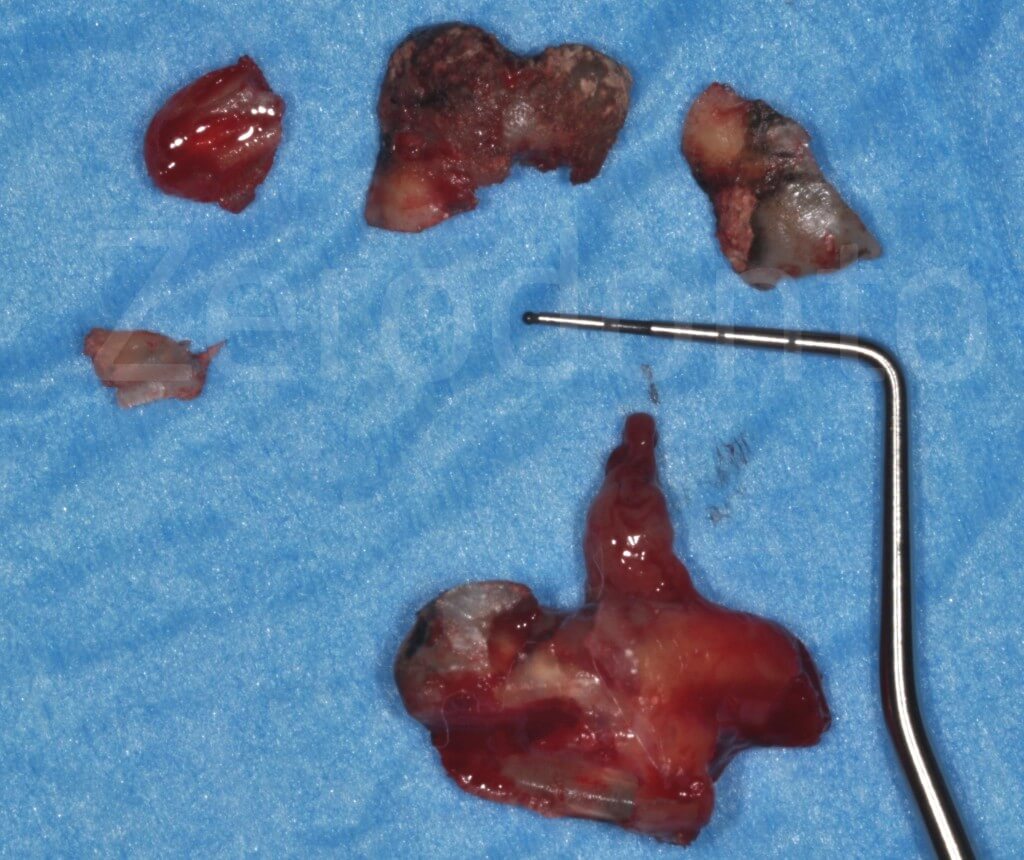

The fragments of the extracted tooth.

The wound is still healing by secondary intention, one month later. The postoperative period was uneventful.

CASE 2

Pain in a 73 year-old female patient

Partially impacted mandibular left third molar, carious, with risk indicators for the inferior alveolar nerve: the intersection of alveolar canal and roots is unusually high.

The risk of neurological damage depends on the relationship between the alveolar canal and roots of the impacted tooth and the patient’s age (Haug et al, 2005).

Complexity factors: age (atrophy of the residual ligament), extensive caries (lack of leverage points), alveolar nerve at the height of the furcation.

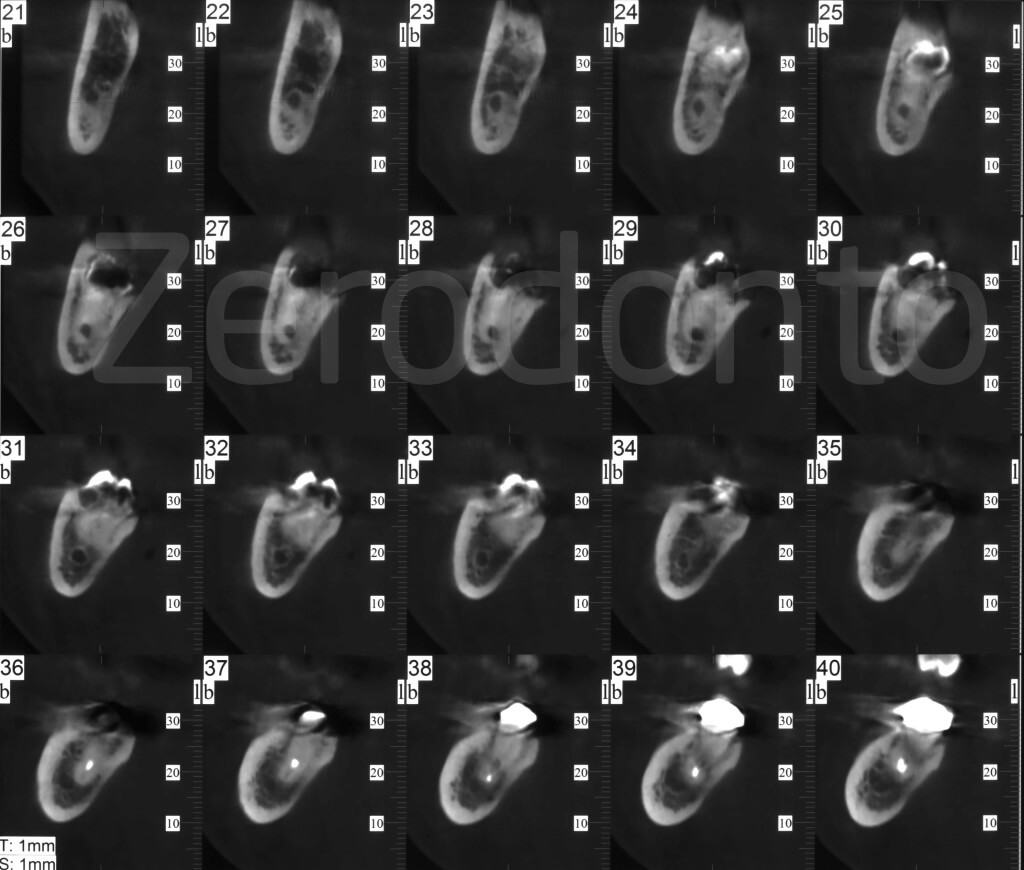

Despite the tooth being superficial, a CB is required to study the relationship between the roots and the alveolar canal: in particular, it is necessary to know if the canal is buccal, lingual or between the roots.

The CB shows the alveolar canal that passes through the roots.

Strategy to address the complexity factors

- atrophic ligament:

use of sonic instruments

- alveolar nerve between the roots:

creating a cleavage with sonic tips and gentle luxating maneuvers using the microscope

Technical steps in the video clip

- Elevation of a triangular flap with distal releasing incision

- Separation and removal of the crown

- The roots are mobilized by thin elevators: the initial subluxation avoids the need to apply excessive force to the elevators in the proximity of the neurovascular bundle

- A new cleavage is obtained using sonic tips or thin burs where the elevator cannot be inserted between the tooth and bone lever

Technical steps in the video clip

- The roots are separated from the nervous vascular bundle, which is seen as a whitish cord

- The sonic instrument (Komet, SFS90M / D) is used to create a clear cleavage plane where a small root elevator can be inserted

- Removal of the distal root

- The mesial root can also be dislocated gently, using the surgical microscope

- The root comes out by bypassing the nerve

The integrity of the neurovascular bundle that crosses the empty socket can be verified after the extraction.

The patient had 5 days of impaired lip sensitivity which completely recovered 15 days after surgery.

CASE 3

Recurrent keratocysts (Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor) in a 16 year-old girl

Radiolucent lesion around the root of the left mandibular lateral incisor.

The patient reported a previous surgery for cyst removal, which occurred one year earlier. The histopathologic diagnosis was: keratocyst.

Complexity factors

- aggressive lesion with high risk of recurrence

- involvement of the roots of adjacent teeth

- thin periodontal biotype

The lateral incisor responded weakly to the vitality test and underwent endodontic treatment.

Strategy to address the complexity factors

- high risk of recurrence:

complete removal of the lesion and treatment of bone walls with Carnoy’s solution (4,5)

- involvement of adjacent roots:

surgical microscope and microsurgery instruments

- thin periodontium:

marginal incision without vertical releasing incisions

4. Sharif et al. Interventions for the treatment of keratocystic odontogenic tumours (KCOT). Cochrane Data Base Syst Rev, 2010.

5. Stoelinga PJ. The Management of Aggressive Cysts of the Jaws. JOMS, 2012.

Technical steps in the video clip

- Excision of the lesion with preservation of the bone walls

- Treatment of residual cavity with Carnoy’s fluid

The protocol involves a follow-up with clinical and radiographic controls every year up to 10 years.

Clinical follow-up 3 years later.

Radiographic follow-up 3 years after surgery.

RECOMMENDED REFERENCES

Arcuri C, Bartuli FN, Germano F, Docimo R, Cecchetti F. Bilateral anesthesia into Spix’s spine. Ten years’ experience. Minerva Stomatol. 2004 Mar;53(3):93-9.

Brown R, Rhodus NL. Epinephrine and local anesthesia revisited. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005.

Haug R H, Perrott D H, Gonzalez M L, Talwar R M. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Age-Related Third Molar Study. J Oral Maxillofac Surgery 2005.

Rood & Shehab. The radiological prediction of inferior alveolar nerve injury during third molar surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990.

SEDENTEXCT Project 2016.

http://www.sedentexct.eu/content/guidelines-cbct-dental-and-maxillofacial-radiology

Weltman N, Al-Attar Y, Cheung J, Duncan D, Katchky A, Azarpazhooh A, Abrahamyan L. Management of Dental Extractions in Patients taking Warfarin as Anticoagulant Treatment: A Systematic Review. J Can Dent Assoc 2015.